The Ultimate Underdog Playoff Best Ball Guide

Playoff best ball contests are some of my favorites because a lot of our competitors draft dead teams. In last year’s Gauntlet contest, 13% of teams drafted after the playoff bracket was released had no chance to win 1st place. In season-long best ball, you can mostly follow ADP and draft a team that, while not optimized, could theoretically win. That’s not an option in playoff best ball contests.

Let’s start by digging into the rules and prize structure of Underdog’s main contest, The Gauntlet. Then, I’ll walk through all of the data from last year to see what we can use to win this year.

Rules and Prize Structure

In Underdog’s playoff contests, you’re drafting against five other competitors who each select 10 players. Each week, your five highest-scoring players hit your lineup. That includes one QB, one RB, two WRs or TEs, and one FLEX. This year, the weekly advance structure for The Gauntlet is as follows: one of six teams in the wildcard round, one of six teams in the divisional round, one of five teams in the conference championship round, and then a 500-person final during Superbowl week. The scoring is not cumulative, meaning you have to score well in each individual week to advance. And the prize structure is very top-heavy, with 1st place winning $500,000 compared to just $500 for making the finals.

What did he mean by Dead Teams?

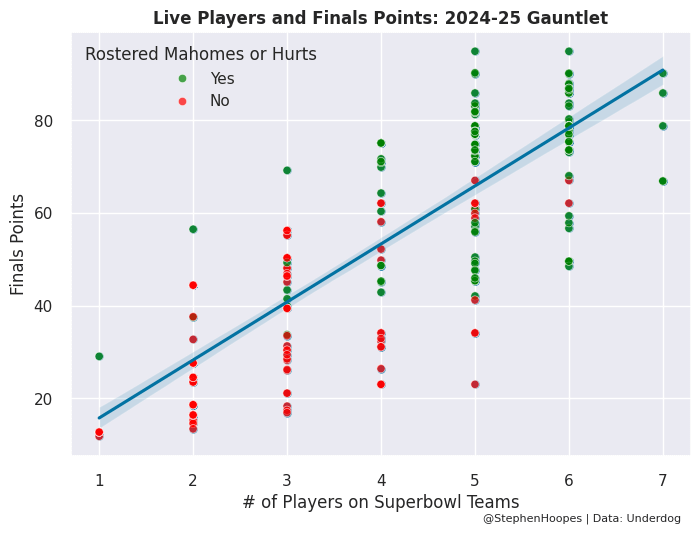

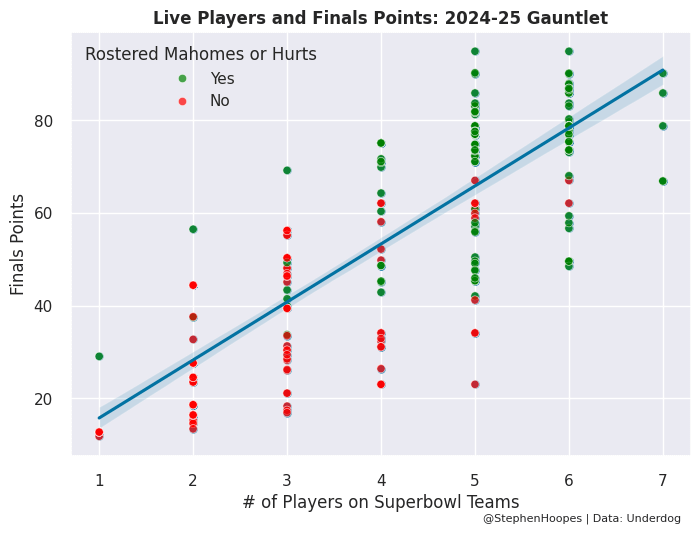

I mentioned in the intro that 13% of teams drafted last season, with full knowledge of the playoff bracket, were immediately ruled out from 1st place. If there is one thing to focus on in this entire article, it’s the graph below. Each dot is a team that made last year’s Gauntlet final. The x-axis shows the number of players each team had in the Super Bowl matchup (i.e,. they were on the Chiefs or Eagles). And the y-axis shows how many points each team scored in the finals.

The trend is abundantly clear. The more players you have in the Super Bowl matchup, the more points you’re likely to score and the more money you’re likely to win. The top-performing team with four or fewer players in the Super Bowl matchup finished in 82nd place last year. And it’s even more dramatic when we include QBs in the analysis. Each green dot on the graph means the team drafted either Patrick Mahomes or Jalen Hurts (i.e., the two starting QBs in the Super Bowl last year). A red dot means the team didn’t have either QB. The top-performing team without either Mahomes or Hurts finished in 113th place last year.

Our primary goal when drafting is to select a team that can fill out a full lineup during Super Bowl week. That means we need at least one QB, one RB, two WRs or TEs, and one FLEX from the two teams that will play in the Super Bowl. Now, we don’t know which teams will be in the playoffs at the time I’m drafting. So, there is some grace there when we’re trying to sort through playoff odds.

But last year, after the playoff bracket was determined, 13% of teams in The Gauntlet still could not fill out a full lineup during Super Bowl week. That was for any possible Super Bowl matchup, not just the one that ultimately happened. They didn’t have a single set of players from any NFC and AFC team combo that could get one QB, one RB, two WRs or TEs, and one FLEX. When you compare that to the 11.1% rake, it means the playoff contests are essentially rake-free.

Roster Construction

So, our ultimate goal is to have a full lineup of players during Super Bowl week. But we do need to advance to the finals to have a shot at the money. Most of the analysis from this point is going to look at what worked well last year. A big caveat to this kind of analysis is that this worked well last year. Data like this is more often descriptive (i.e., telling a story about what happened in the past) than predictive of what will happen in the future. But let’s parse out those differences as we go through.

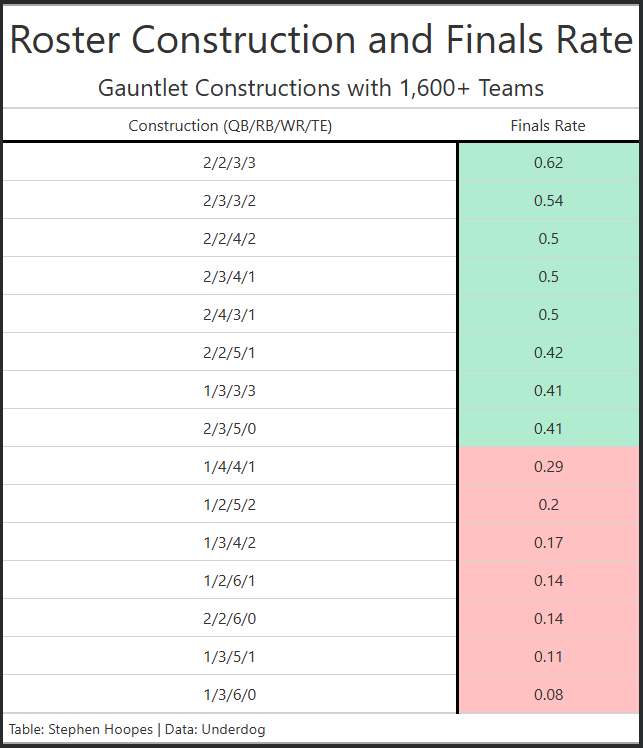

Up first is roster construction. By that, I just mean how many players in each position group should you select? The table below shows the most commonly used roster constructions from last year, along with their finals advance rate as a percentage. The thing that stands out the most to me is QB. RB is pretty commonly two to three players, while WR and TE are a bit all over the place. But the top six constructions that advanced to the finals most frequently had two QBs.

The advantage of drafting a team with one QB is that it opens up another positional player to hit your lineup during the Super Bowl. But at least based on last year, we’re sacrificing a ton of advance rate in the process. I’ll say this a lot through the article, but this could of course just be descriptive and specific to last year. But given how clear it was, I’m personally leaning toward more two-QB builds this year, with two QBs drafted through round eight optimal last season.

Stacking

It’s not a best ball contest if we don’t discuss stacking. Stacking is infinitely more important in playoff best ball than in season-long contests. Our primary focus is to maximize the number of players in the Super Bowl matchup. By definition, that means we want a lot of players on two specific NFL teams. So, should we just draft five players on one NFC team, five players on one AFC team, and call it a day?

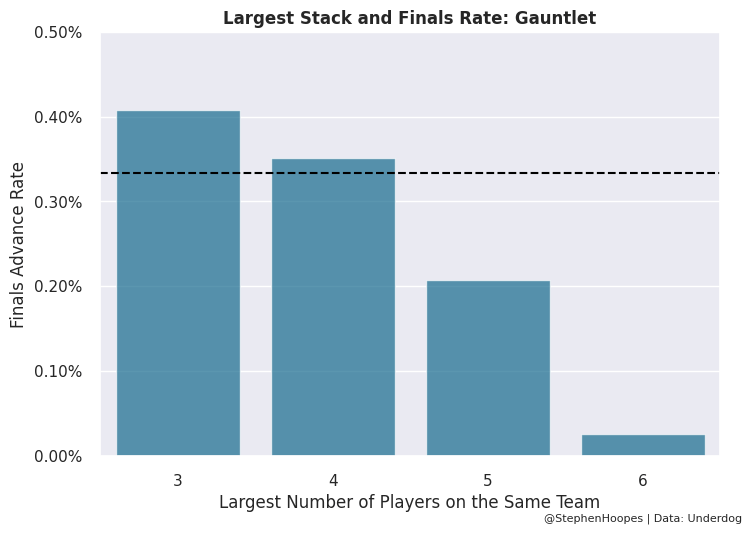

The data doesn’t support that. The x-axis of the graph below shows the largest number of players from one NFL team on a drafted team’s roster. And the y-axis shows their finals advance rate. Once you get past five players on the same NFL team, your chance to make the finals really drops. I think there are two reasons for this. The first is that the fifth player drafted on the same NFL team in this style of contest is probably not very good. They’re not likely to hit your roster and help you advance.

And that leads directly into the second reason, which is that we still need to advance each week. The way the ADP shakes out, there are often very talented players available late in drafts because their team’s odds of making the Super Bowl are very small. Perhaps an example would help. Last year, the Ravens had very good odds of making the Super Bowl, while the Texans did not. Would you prefer to have your fifth-Raven Justice Hill on your roster or Nico Collins? Based on this, I’d much prefer Collins. But it’s this balancing act between advancing to the finals and having the firepower to win it all that makes these contests great. And that's especially true if you think one of the NFL teams with a bye in the first round of the playoffs will ultimately reach the Super Bowl.

ADP

I’m going to talk out of both sides of my mouth when it comes to ADP in playoff best ball. On one side, ADP doesn’t matter at all. In each team you draft, you’re building out a specific scenario of teams that will make the Super Bowl. In rare cases where all of your competitors understand the rules and aren’t building out an Eagles stack (as an example), then Eagles players are likely to fall to you later than ADP suggests. But if you’re competing with other drafters for players on the same NFL team, then you’re going to have to reach relative to ADP.

From the other side of my mouth, I’m going to say that getting ADP values still matters in playoff best ball. And that’s because starting in round two, we’ll be competing against teams that might look very similar to our own. We want to build an otherwise similar team at a cheaper cost than our competitors. That hopefully gave us the flexibility to take an expensive piece that isn’t part of our Super Bowl scenario, but that could be critical to advance.

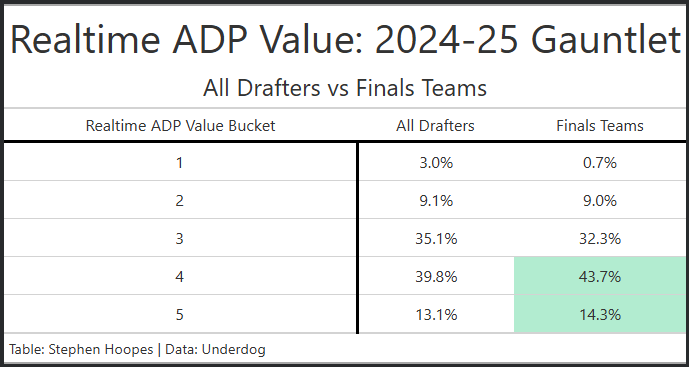

The table below buckets drafters into how well they managed to capture real-time ADP value. Essentially, did they tend to take players earlier than the ADP suggested at the time they drafted or later? Teams in Bucket 1 largely ignored ADP and took players whenever they wanted, especially in the earlier rounds. And teams in Bucket 5 took falling value. It’s again a pretty clear trend; it’s ideal to grab ADP values while still keeping your specific Super Bowl scenarios in mind.

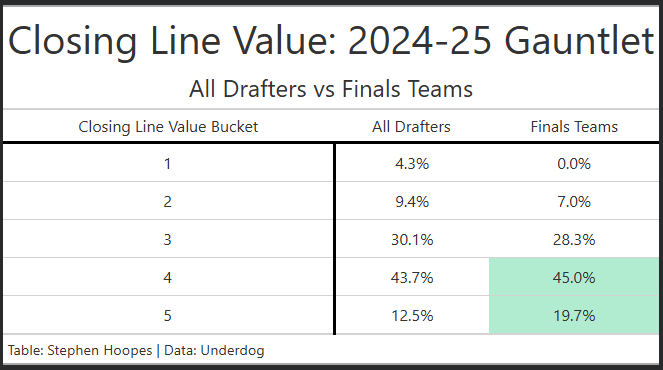

And it’s even more dramatic for closing line ADP value. Closing line value is the difference between when you drafted a player versus what their ADP looked like right before the playoffs started. One of the biggest reasons for this, in my mind, is due to the timing of when playoff contests open versus when the playoff bracket is finalized. For example, the Cowboys currently have very low odds of making the playoffs. If you draft right now, you’d be able to get very cheap prices on CeeDee Lamb, George Pickens, etc, relative to their talent and fantasy scoring potential. If you load a team up with Cowboys and they do end up making the playoffs, you’ll have almost guaranteed yourself a top team in terms of closing line ADP value.

Uniqueness and Diversification

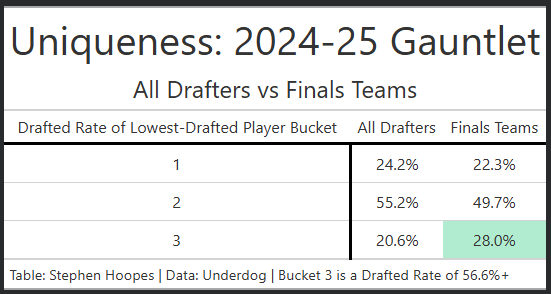

Let’s close things up with a couple of quick thoughts on uniqueness and diversification. I’m defining uniqueness as the drafted rate of the player on your team that was drafted the least often in the tournament. The idea behind taking a player that isn’t frequently drafted is to separate yourself from the competition in the finals. If your rarely-drafted player has a huge game in the Super Bowl, then you set yourself up well to take one of the top prizes.

But this comes at a cost to advance rate. The table below groups teams into three buckets. Bucket 1 teams took at least one player that almost no one else was drafting in the tournament. While Bucket 3 teams stuck with players that were selected in most drafts. The less-unique teams were over-represented in the finals. So, this is mostly to say that you'd better be right that your low-drafted player will hit in the Super Bowl, or you’re hurting your advance rate for no reason.

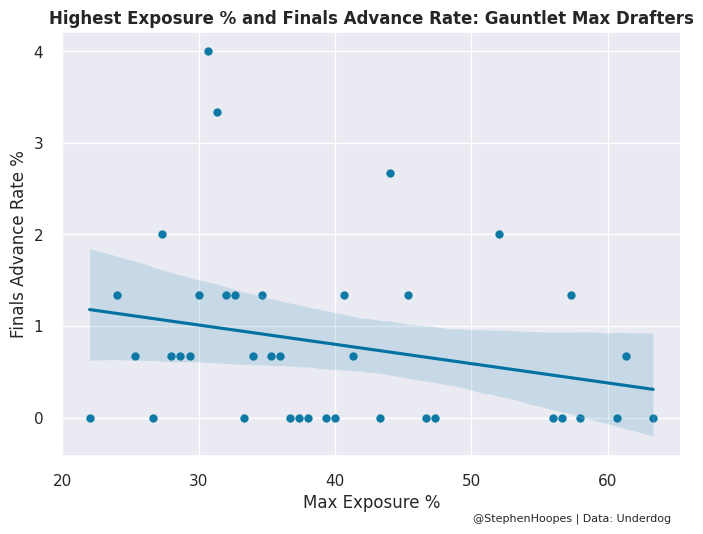

And this diversification section is mostly for people who plan to draft a lot of playoff best ball teams. Each dot in the graph below is someone who entered last year’s Gauntlet contest 150 times. The x-axis represents how often they drafted their most-drafted player. For example, if your most-drafted player was Jahmyr Gibbs and you took him on 60% of your teams, your max exposure percentage was 60%. And the y-axis shows the percentage of their teams that advanced to the finals.

You typically see a downward trend in graphs like this, just like we’re seeing here. Generally, as your max exposure percentage increases, your success in advancing to the finals decreases. But you’ll also typically see some of the highest advance rates among drafters with a high max exposure percentage. That’s because there is a risk/reward tradeoff in selecting one player a ton of times. If that player hits in a massive way, then you’re going to have a great year. But if they bust or get injured, then your playoff best ball season is likely over. Similar to uniqueness, you had better be right.

Bottom Line

• I included the same graph from earlier in the article again because it’s that important.

• Our primary goal is to draft a team that can fill out a full roster during the Super Bowl when all of the money is won.

• Each of the top-scoring 81 teams in the finals of last year’s Gauntlet had five or more live players during the Super Bowl, while the top-scoring 112 teams each had one of the QBs playing the Super Bowl.

• A big benefit to playoff best ball contests is that our competitors don’t understand the rules, with 13% of all teams drafted last year with full knowledge of the playoff bracket not able to fill out a single Super Bowl lineup in any possible matchup.

• The top-six roster constructions with the best finals advance rates last year all had two QBs, making me lean in that direction this year despite missing out on one additional position player to go nuclear during the Super Bowl.

• At least last year, you really started hurting your finals advance rate when you hit five players drafted from the same NFL team.

• ADP is much less useful in playoff best ball contests, but we still care about ADP value because we want the best version of what could be a similar team that we’ll face in the divisional through Super Bowl rounds.

• Finally, be careful with selecting players that are rarely drafted or selecting one player in a ton of your drafts, because in both cases, you had better be right or you’re sacrificing your probability to make the finals for no reason.